Now that you’ve made it to the windward mark, you have reached the final section of the lap/race approaching the final drag to the finish. The downwind leg to the leeward mark is usually a fast-paced, sprint race with high tensions and lots of pressure for the lead boats as it is almost always the final leg to the finish. The speed at which FW boards travel makes tactical decisions more difficult as everything happens at a rapid pace. With the downwind leg only making up 15% of the total race elapsed time, there isn’t as many tactical decisions that need to be made however the few that do have to be an instant reflex response. This week we continue with the articles on Advanced Tactics by getting you from the windward mark to the leeward mark, looking at a few very important rules as well as some tricks you can have up your sleeve to keep your lead into the leeward mark.

When approaching the windward mark, always remember the three key rules:

- If you are lifted markedly heading to the mark on Starboard, gybe immediately on to port after the mark.

- If you are knocked markedly heading to the mark on Starboard, stay on the starboard tack to get the most out of the knock.

- The side of the course which is favoured on the upwind leg is generally the side to take on the downwind leg.

That shouldn’t be a “decision” on the racecourse; it should be a reflex. The only revision to the first two rules is if there is a favourable side of the course due to a geographic, tidal or other influence that creates this favoured side.

Knowing & Understanding Your Angles

The key to dramatically improving your downwindtime around the course: understanding what angles you can sail in what windstrengths. Simple huh?

Not exactly. Most sailors have a reference point on their boom, which is usually a perpindicular line to the mark (its easy to visual 90 degree angles) whereby when they see the leeward mark through their sail they will gybe when it lines up roughly with this boom reference point. I’m here to tell you that that isn’t specific enough and can allow boats in close proximity to gybe earlier/later than you and punish you into the leeward mark. A good way to combat this is to research the angles you can sail downwind in various windstrengths and then learn how to quickly gauge that particular angle by sight.

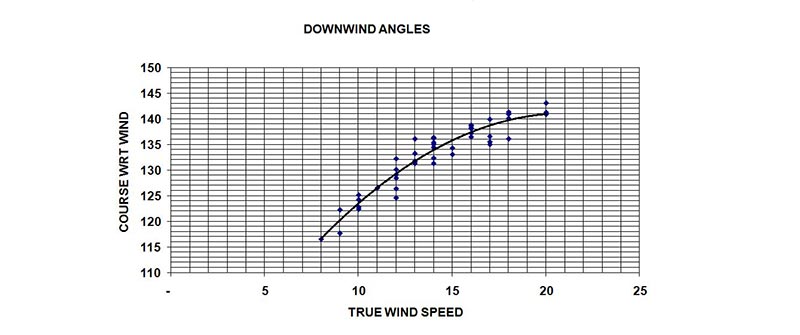

To do this accurately you are better off using a GPS unit to analyse tracks of your sailing in various windstrengths (something we will be writing about here very shortly). Here on the left is a chart I have made for angles that I can sail in relative windstrengths. Using about 3-4 months of GPS data from sailing FW in various windconditions, I have plotted the different downwindangles I have achieved against the wind speed on that particular day. Obviously, there are slight performance differences each session in the same windstrengthbut using a mean trend-line we can get a good estimate of what angle I can sail in what windstrength.

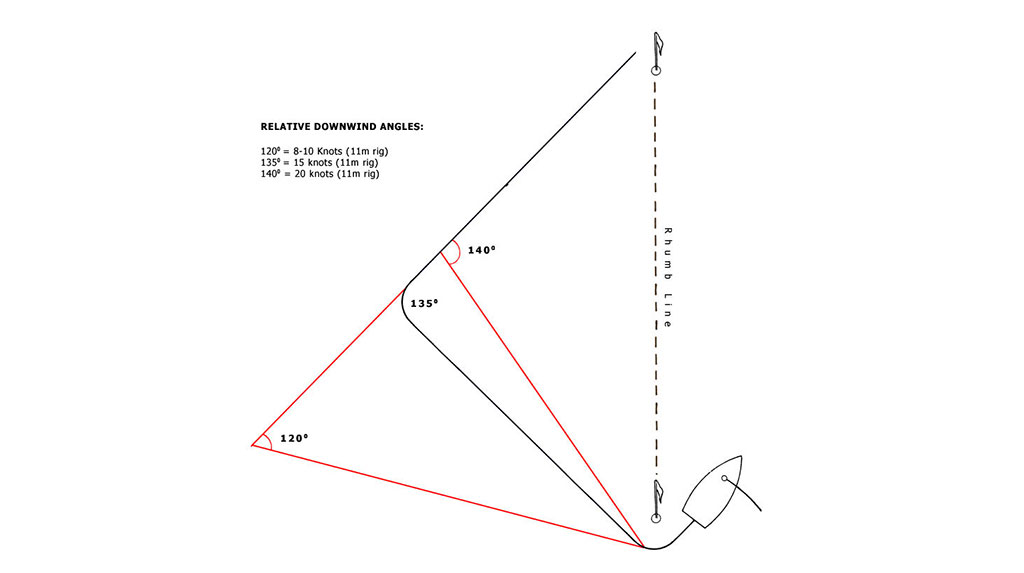

You only need to know a general group of angles, for example 8-12 knots, 15 knots, 20 knots etc. If you can learn what angles you sail in these windstrengths you can improve your downwind laylines immensely. For example, using my chart above, I see that I can usually sail downwind at 120 degrees with an 11m sail in 8-10 knots of breeze (see figure to the left for a visual representation of the Downwind Angles chart). I have a good idea of what 120 degrees (not to the nearest degree, but roughly enough that I can make an informed decision about where to gybe) looks like when I line the leeward mark up through my sail and I have a good idea of what 8-10 knots feels like when I sail my 11m. With that in information in mind, if you are the leading boat on the downwind, you can know that when you gybe it will be the perfect layline and that if the guys behind you have gybed any earlier, they are going to have to wipe off considerable speed to get down to the mark or to put in two extra gybes; you have protected your lead.

Protecting Your Lead

As Bethwaite states, a “boat with a small righting moment (like a Laser) cannot deflect wind too much, but a more powerful boat such as an 18ft skiff (or an FW board), deflects the wind an incredible amount”.

With this in mind, the most important weapon to protect a lead on the downwind run is to keep your pursuer always in your dirty air and disturbed water. If your pursuer attempts to pass you to leeward (that is, inside you), if possible you can bear off slightly and use your dirty air and wind-shadow to slow the passing boat. It is very difficult to pass on the inside unless the passing boat can sail significantly deeper than the lead boat as you have to sail through the worst of the air deflection from the leading boat, which harms downwind performance immensely. Should the pursuer try to pass to windward, it only requires the lead boat to luff him to windward and force him deeper in to the hopeless position.

In the case of several pursuers, as Manfred Curry would suggest: “one directs one’s chief attention, as on a beat to windward, to the one nearest”.

Know Your Competition / Force the Gybe:

The next tool in your downwind weaponry is your laylines. Get them correct and you’ve made it very difficult for the pursuing boat to pass you. Get them wrong andyou will find yourself sitting in someone’s dirty air at the leeward mark.

Everyone uses a different setup and may take a different fin and so it’s more than likely that in your fleet there will be some who are faster and can sail deeper than you on the downwind (if not, you have no excuses for not winning each race). To protect a lead it is important to have an idea of what angles the sailors behind you can sail. If you are in an unknown fleet, it should only take you one race or so to work this out. If your main competition can sail deeper than you at a similar speed, there are preventative steps you can take to protect your lead to the leeward mark.

Getting aroundthe windward mark first on the last lap, withonly the downwindto sail to the finish when the guy 10m behindyou is considerably faster than you downwind is a common and frustrating occurence (I’ve had my fair share). Despite the formentionedtactics above to protect your lead, withthe speeds an FW board travels at, blocking the sailor behind you is not always as easy as it would seem on paper as pursuing sailors can change positions from the hopeless position to a dominant position in less than a second in windy conditions and it is difficult to keep your eyes on the water ahead as well as on what your pursuer is doing. One of your few options to protect your lead in this instance is to play on your opponents mindset that he can sail deeper than you downwind…

The pursuing boat, knowing that he can sail deeper than you, most likely will gybe when the leading boat gybes and back his ability to sail deeper andfaster, hoping to use his better angle to pass on the windward side and use his wind-shadow on the leading boat as he controls the lead into the leeward mark. If you know your downwind angles in the particular windstrength, try gybing earlier than is possible to make the leeward mark. If the trailing boat is true to form, he may gybe when you do and both of you now will have to make an extra 2 gybes into the leeward mark. You know this before he does, so by heading a little higher out of the gybe you can put him into your dirty air and hold him in the hopeless position andforce him to have to gybe away to get clear air. This tactic is best when you are in a clear position with 1st/2nd together as it may allow the 3rd/4th boats an opportunity to gain if they are close enough and sail the layline correctly. If your pursuer does in fact gybe again to get away from your dirty air, you will both have the same amount of gybes to do however when you meet at the leeward mark you will be approaching on starboard to make your final gybe and will have right-of-way (provided you can fit your gybe in before he gets to you).

Gybing Strategy:

Once you’ve practiced enough, you should be able to gybe and keep on the plane all the way through on to the next tack. In winds over 12 knots (ie, when you are able to consistently plane out of each gybe), a good gybe takes only 3-4 seconds to complete and regain full speed. This is considerably less time than a tack and usually you don’t lose much angle as when you are pumping out the gybe you can point downwind much further than you can actually sail to promote a quick gain back to full speed. In 10 seconds a FW board travels about 80m so you are only losing 25m or so in each gybe. That seems like a lot but in a normal course using a 1.3km rhumb line (shortest distance from windward to leeward mark), 25m is a small disadvantage compared to the advantages made in sailing the correct course downwind rather than the one with the least amount of gybes.

Sailing in onshore conditions in consistent winds, usually the bulk of the fleet sails the downwind run on starboard, taking one gybe to the leeward mark. This happens even in international fleets. In most cases (FW World Championship locations like Leba, Poland; Gangnueng, Korea; Forteleza, Brazil; Melbourne, Australia all had courses like this) the single-gybe run forces the sailors to sail right to the beach where they gybe on to port tack andfollow the beach into the leeward mark close to shore. 9/10 times there is considerably less wind close to the shore as breaking waves, sand dunes, trees, buildings or the land/water temperature differences creates turbulence for the wind andoften forces the clear wind into the air (away from your sails) thus creating light spots along the beach. A sailor who sails into the beach andtakes a little longer to get on to the plane out of the gybe, coupled with the tight angle he will have to sail to get out of the shore-zone and back into the clear air will lose far more than 40m versus a sailor who put in the extra gybes and stayed in the stronger winds out to sea.

3 Gybes? Make It Count:

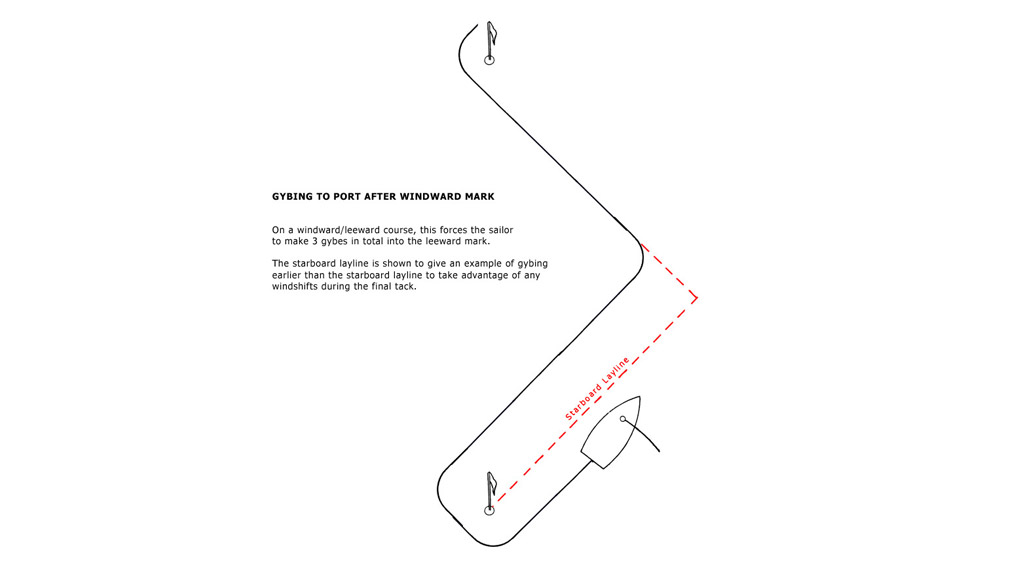

One thing to note is when you do gybe on to port around the windward mark (you have a minimum of 3 gybes to complete on a standard windward/leeward course now) you should always complete your second gybe earlier than the starboard layline to head towards the leeward mark. This allows you to take advantage of any wind direction changes or gusts (see diagram to the left for a visual reference). The difference in downwind angle in 1-2 knot differences of wind is substantial compared to the same wind differences and upwind angle (which is minimal). Approaching the leeward mark on starboard with a final gybe to put you back on to port to round the mark it is important to not oversail the starboard layline as having to head up to make the leeward mark gybe wastes all your advantage in having sailed a different course to the other sailors. You are going to have to gybe back on to port anyhow, so does it make a difference whether its 2m from the leeward mark or 40m?? Better to be safe and always sailing a deep downwind angle than to overshoot and have to head up (crucifying your downwind VMG).

Attacking From Behind:

Assuming two boats are equal in downwind speed, it is difficult but not impossible to pass the leading boat on the downwind leg. Your two options are to sail a better layline (gybe earlier/later) and get the advantage into the leeward mark or to pass the leading boat either to windward or leeward with superior speed.

Passing to Windward:

The generally accepted better side to pass on is the windward side, as passing on the leeward side you have to sail through the very disturbed air and wind-shadow of the leading boat which is difficult to do unless you have a fairly big advantage in board speed over the lead boat. Assuming you are always sailing as deep as possible on the downwind run, luffing a little will increase your board speed at the expense of angle. Often times, the increase in board speed allows you to keep your downwind VMG the same and can help you pass the leading boat on the downwind as he may be sailing slower to go the deepest angle possible. He may luff you to try and defend this attack but within reason you can continue to luff higher and higher and increase your speed to overtake; its very rare for a leading boat to luff you all the way to a beam reach; and this allows you an opportunity to try to scoot through on the leeward side while he is not watching. This tactic works best for heavier sailors as they are usually faster on a broad reach angle.

Passing to Leeward:

Although more difficult, there are times when this tactic should be applied. The main instance in when you are pursuing a group of sailors. Often times, many in the group will be sailing a slightly luffed course to keep themselves out of the dirty air of the boats around them. Provided you are at a safe enough distance to not be affected by their dirty air too much, sailing a very deep course allows you to get into a controlling position leading into the gybe, as you will be closer to the leeward mark if you gybe at the same time as the leading boats. Despite the obvious disadvantages in sailing in someone’s dirty air, if you can sail inside the leading boats you will get the cleanest air when you gybe on